Designing Experimental Design: From Proposal to Experimentation

- JBeamer's Blog

- Log in to post comments

Written by Dr Jennifer Beamer

Funding: John-Kiernan €500 Award, EXARC

‘Experimental archaeology’ is conceptually understood as a form of archaeological investigation that utilises the process of making to infer how something may have been made in the past, using artefacts and/or historical documents as a source of guidance (Burke and Spencer-Wood 2019; Outram 2008; Schlanger 1996; Stone 2011). This methodology can also be used to explore nuanced topics such as engagement, bodily experience, and behaviour in terms of small- and large-scale discussions. Furthermore, due to the confluence of expertise, it is inherently interdisciplinary. Formulating a concrete structure to an experiment where there may be limited scholarship can present the first significant hurdle to conducting an experiment.

Experimental design is part of the process of performing experimental archaeology, and every experiment will require a tailored approach. This can be the primary focus of the experiment—in terms of exploration—or can be an accessory for addressing a later step in the experimental process. In publications of experimental research, the design is presented as a logical progression of steps, culminating in results that can be analysed against the archaeological record. However, there is little discussion of how the design process occurs when it is time to conduct the experiment. The question I want to answer is “how do you create a cogent design for an experiment?” This blog post will offer an insight into how experimental design works in practice, using an ongoing experiment being conducted by the author.

Experiment premise:

Using my experiment involving spindle whorls from the British Iron Age (link to project plan), I will demonstrate how an imprecise method can be used for solidifying the design for an experiment. Though I have created several experiments in the past (Beamer 2021) with loomweights, the current experiment with spindle whorls cannot use the exact same approach. As well, I will offer broadly applicable advice for keeping track of progress.

The step between having a proposal for an experiment and conducting the experiment will raise questions of how to conceptualise the future action of actually performing the experiment. There is rarely sufficient time to explore all possibilities, yet it is worth strategically planning for several minor questions to be addressed in the process. Therefore, the specific design phase must be approached critically. For example, I know that I will need to make 6-8 replica spindle whorls from Danebury hillfort, but I need to decide which archaeological examples to select for making functional replicas, and why this selection has the possibility to reveal important and significant information. Let’s start with three basic steps to help explain how they impact the design of an experiment.

My first step when beginning the design is to get organised, which includes my digital evidence, such as photos, and physical evidence, such as my raw materials. I create a primary digital folder, such as ‘Experiment 7 2025’ or ‘Spindle Whorl Data 2025’ and create subfolders such as ‘Raw Photos’, ‘Edited Photos’, ‘Experiment Log’, etc. This step makes it easier to keep track of where everything is and allows me to easily create a backup on the cloud/an external drive. This also makes it easier to refer to when making hand written notes and updating the Log.

At the same time, I will make a Word document called ‘Experiment 7 Log 2025’, for instance, and document all my thoughts, decisions, and progress, much like one would show evidence of long division on a maths test. I organise every entry into the Log by date, using Headings in Word to aid with navigation in the document. For those experimenters who prefer to have a soundboard to bounce off ideas, I find this method useful for grounding my thoughts and so that I avoid forgetting fleeting epiphanies. If a duration component is useful for you, consider also creating an Excel document to record how long it takes to complete certain tasks and reference this in your Log. During the later stages of an experiment, I find these logs particularly useful to ensure I remain informed of why I made certain decisions earlier in the process. As well, they are good to revisit during the writing up stage and when discussing future opportunities with further experiments.

Step Two mainly revolves around collating the evidence that inspired me to create this proposal initially, in the form of a working Bibliography. This includes those references which directly contributed to the proposal, as well as those references that may be useful to re-read or for the ease of writing the final publication/conference papers. Additionally, it helps with identifying possible gaps in research as I progress through the experiment, in an effort to be as thorough as possible. Starting the design with a bibliography in this way helps me refine the design of my experiment.

Step Three, record as much detail as possible. Generally, most experiments rarely have the luxury of repetition so it is essential to document and photograph everything. Especially when using materials that may have a unique feature, such as a wool from a specific farm/sheep or chalk for a whorl, take before/after photos for every change made. For my experiment, I have photographed each piece of chalk that may potentially become a spindle whorl. I anticipate some of the chalk being unusable for whorl creation, but once I begin carving into the block, the reductive process makes it impossible to show how sensory experiences may have influenced material choice in the past—some blocks look identical, but they feel different. As well, I plan to record videos of how each one was carved, as part of the documentary evidence which may reveal the material properties of suitable chalk and could provide insight into potential reasons why some chalk whorls were broken in antiquity.

Metadata or tags can also be used to organise these records. This part of the recording system is especially important for those projects which will be deposited into an archive. They can be embedded into the photographs and video footage to ensure they remain well-documented. For my project, which includes a social media component, having this information alongside my visual evidence will be useful for YouTube and Instagram algorithms.

Through the act of organising myself/project, I inevitably rhetorically ask many questions that I would not otherwise think to ask at the proposal stage. Simply, ‘how should I photograph my experiment?’ can result in many different answers. It seems logical to have a photo of my chalk block with a scale, but it also may be helpful to have an ID photo (an arbitrary ID will usually suffice) and one without a scale, which amounts to a minimum of three photos per unworked block of chalk. For consistency, I will create three photographs for each worked version, whether I was successful in making a spindle whorl or not. Consider cinematic photos to emphasise or create a mood or feeling, or to use as part of a theoretical discussion in archaeology. I record my rationale for such decisions in my Log.

Such decisions may not impact the outcome of the experiment, they do influence the quality of the experimental design while developing scholarship surrounding methodology. Documenting each step like this is time consuming, and will factor into the timeline for the experiment and scope of the research questions. Making adjustments to the design at the early stage of an experiment impacts the priorities of certain steps, as noted by Demant (2017). Time allowances can be reallocated as the experiment progresses, though anticipating how information will be recorded/documented will aid an experimenter in conceptualising realistic goals/milestones.

Using my working bibliography, I can easily examine the existing scholarship, consider my selection of spindle whorls from Danebury, and record where the inspiration came from in the Log. Since I have gathered all my useful resources into a single place and decided on a system of organisation, the process of refining my precise protocol for the experiment design can begin.

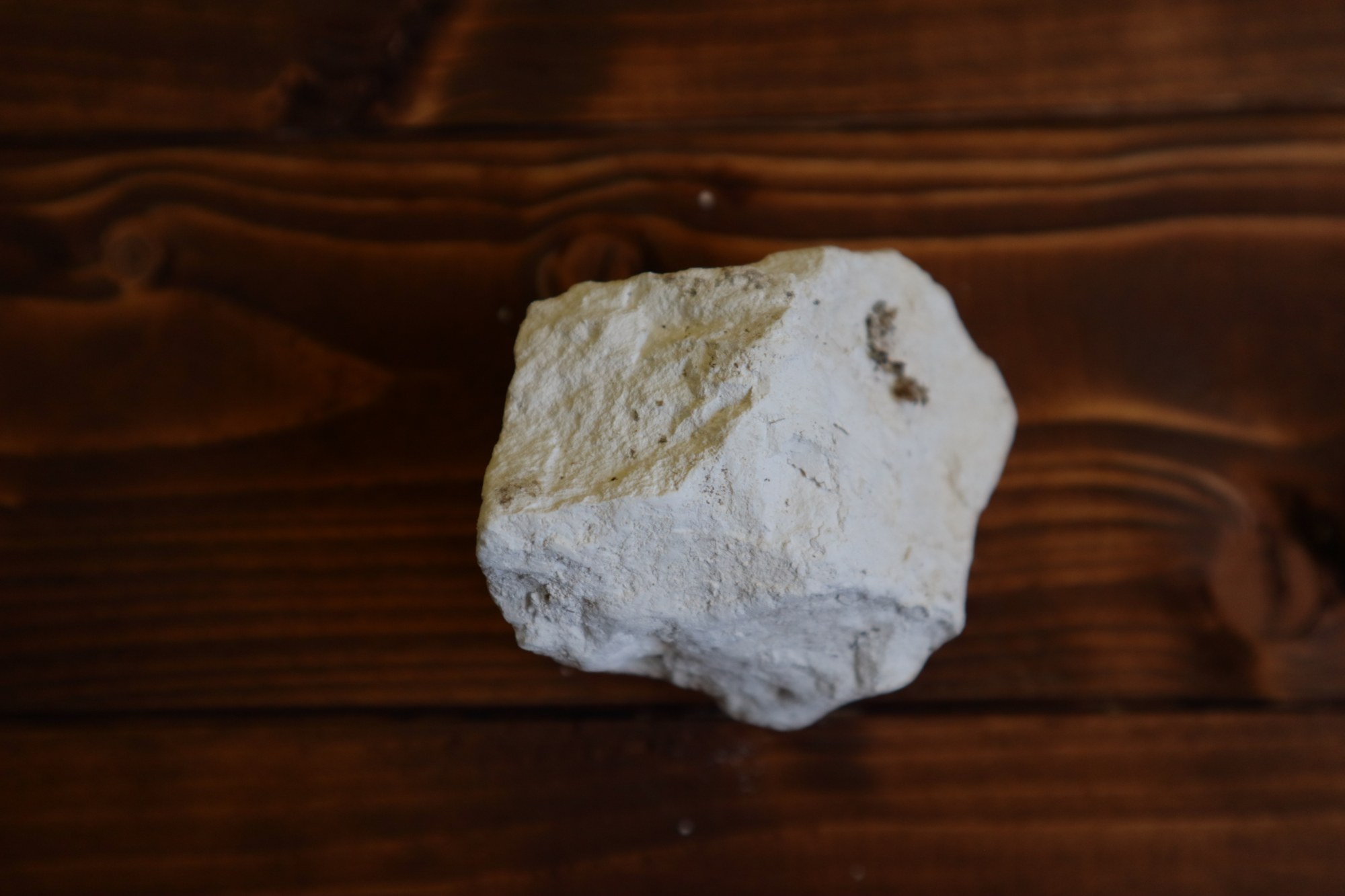

Below is an excerpt of my Log, which illustrates how this slightly imprecise system works for helping an experimenter solidify their design concept:

Chalk selected for the experiment was taken from chalk bearing regions of southern Britain, primarily in Wiltshire. The blocks were taken from a variety of chalk sources, increasing the likelihood that it will represent a typical experience of an Iron Age person who may have selected chalk from a variety of nearby chalk quarries (for example, Danebury hillfort and Suddern Farm). Some pockets of chalk will be purer, while others may be impregnated with more limestone. This can be estimated by ease of carving but is otherwise unscientific. The goal for this experiment, however, is not for accuracy of selecting and processing raw materials into functional tools based on archaeological examples, it is to focus on the spun yarns made from those examples.

Chalk I have collected:

- 537.5g

- 499.1g

- 204.3g

- 181.4g

- 177.3g

- 152.8g

- 122.4g

- 97.5g

From an observational experience, the difference between the 97g and 204g blocks were noticeable, but the 122g-204g blocks was less noticeable. This may be due to the shape, where the blocks in the 122-204g range were similarly rectangular and difficult to discern as different in mass. That said, the difference between the 499g and 537g blocks seemed more noticeable, likely because there were just two at that range to compare. Anecdotal though it is, it may be that Iron Age people who made tools used shape and feel to gauge whether the final products would be ‘the same’. As an educated guess, then, it seems reasonable that if the 122-204g were carved down into spindle whorls, they might all be used interchangeably to make the same gauge/twist degree yarns.

From an overview of searches, it also seems like there is little to no information relating to carving chalk into utilitarian tools (like a spindle whorl might be). Therefore, it will be essential to include a full write up of the process of carving chalk into spindle whorls and relevant observations of the process.

Other aspects to record during the carving process:

- Friability (especially when creating the perforation); chalk dust?

- Tools used (paring knife to substitute for IA equivalent?)

- Stages (should it be cut wet/dry? Rough shaped first, then perforation made, then polished into final shape?)”

The Log is an excellent vetting ground to pontificate without retaliation or embarrassment over one’s ideas. In this excerpt, I noted that my rationale for picking chalk in the way I did may relate to how Iron Age people selected their materials, but is unscientific mainly because I have no budget for a chemical analysis of the archaeological examples or my replicas. In another view, this minor question could become a future project and involve other specialists/collaborators. Still, it is worth observing my sensory experience of this process as it felt relevant. The Log documents your precise thinking process and allows you to formulate the actions you will take throughout the experiment. Later, it provides an excellent scaffold when recounting the exact steps/procedures/outcomes/decisions during the write-up phase.

I recognised a gap in my knowledge relating to how I might carve chalk, and took this opportunity to seek out any existing publications on the matter. Given the paucity of information, I decided to include extra details about the carving process and use those results as part of the experimental design. Again, this informed my decision about how to visually document this information. Photos are an insufficient method of recording ‘how to carve a chalk spindle whorl’, and my sensory insights are important for expanding scholarship on haptic observations.

I have only selected two spindle whorls as my goal to replicate at this time. I anticipate having a third whorl selected before I begin carving anything, but wanted to allow myself time to consider which Danebury whorl that might contribute new knowledge (Grömer 2005, 111). Though I have solidified much of my experiment design now, it is important to convey that refining the design of a project does take time and may be ambiguous, and remain an evolving process throughout the experimental process, yet can be aided by the guidance offered above. Whether you are an experienced experimenter or exploring the utility of experimental archaeology for the first time, it is my greatest hope that you find this advice useful.

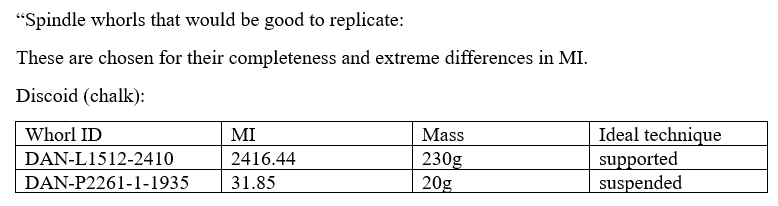

Chalk block weighing 177.3g. Paper label with sufficient area to record other identifying information throughout the experiment.

Simple image of chalk block. This photo may be useful as part of a publication or reference collection.

Chalk block pictured with a scale. This is useful for any digital measurements as well as for publication.

About the author:

Dr Jennifer Beamer completed her doctoral thesis in 2022 on the topic of textile tools and their deposition, using Danebury hillfort and surrounding environs as the study area. Subsequent research has focused on refining the new research raised initially in the thesis, continuing experiments with loomweights, and compiling new data for the production of a monograph.

The John-Kiernan grant provided to the author is being used to conduct new experiments involving spindle whorls, aimed at expanding knowledge of this important step in the textile production chaîne opératoire and creating a dynamic understanding of those choices made which impact subsequent material affordances.

Bibliography:

Beamer, J. (2021). Making prehistoric cloth: Experimental archaeology and experiential results. Assemblage: EAStS proceedings, 28 February 2020. University of Sheffield, pp.14-23. (Accessible at: https://assemblagejournal.wordpress.com/2020-easts-proceedings/).

Burke, C. and Spencer-Wood, S.M. (eds.) (2019) Crafting in the World: Materiality in the Making. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Demant, I. (2017) Making a Reconstruction of the Egtved Clothing. Archaeological Textiles Review, 59, pp. 33-43. (Accessible at: https://atnfriends.com/index.php/2017/12/01/atr-59/).

Grömer, K. (2005) ‘Efficiency and technique—Experiments with original spindle whorls’, in Bichler, P., Grömer, K., Hofmann-de Keijzer, R., Kern, A., and Reschreiter, H. (eds.) Hallstatt Textiles: Technical analysis, scientific investigation, and experiment on Iron Age textiles. BAR International Series 1351. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Outram, A.K. (2008) Introduction to experimental archaeology, World Archaeology, 40:1, pp. 1-6, (DOI: 10.1080/00438240801889456).

Schlanger, N. (1996) ‘Understanding Levallois: Lithic technology and cognitive archaeology’, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 6(2), pp. 231-254.

Stone, E. (2011) ‘The role of ethnographic museum collections in understanding bone tool use’, in Baron, J. and Kufel-Diakowska, B. (eds.) Written in Bones: Studies on technological and social contexts of past faunal skeletal remains. Poland: Institute of Archaeology, University of Wroclaw, pp.25-37.